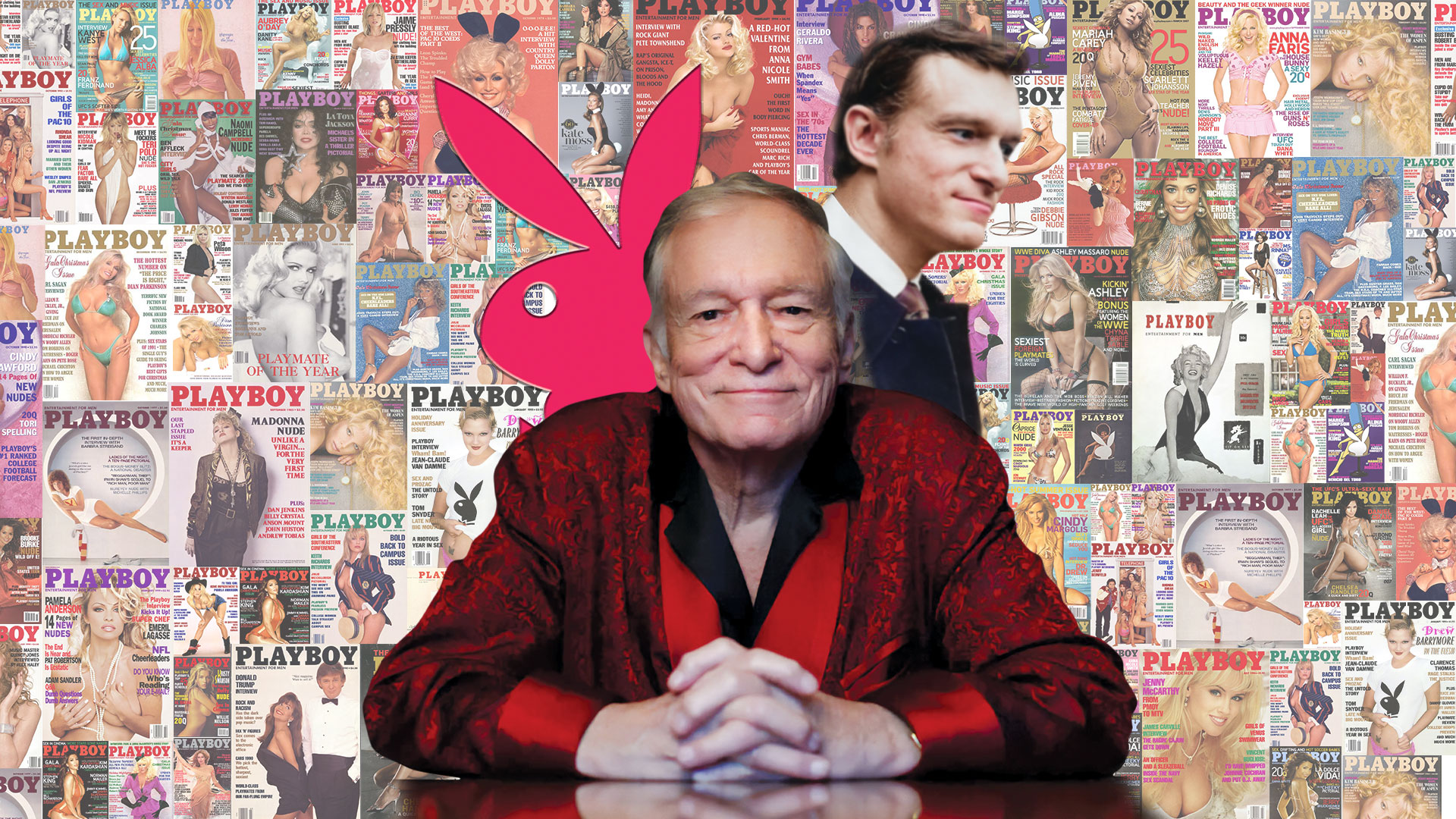

Beyond Bunny: How the late – and lamented by some – Playboy millionaire Hugh Hefner shifted the cultural landscape

The recent sale of Hugh Hefner’s personal heirlooms and the Playboy archives has highlighted once again the huge historical and cultural impact this libertarian had on America and society the world over. Hefner was a one-off, a complex man who overtly encouraged the pursuit of pleasure, and to the astonishment and displeasure of many, wielded immense influence on modern culture.

Raised in the conservative 1930s, Hefner exhibited a creative streak from a young age, setting up a school magazine for which he provided a stream of cartoon strips. During his formative teenage years, he chaffed against social restrictions on matters like sex and immersed himself in popular culture. Considered a social high-flyer at school, he loved movies, cartoons, magazines, dancing and swing music. Enlisting in the army in 1944, he contributed to military newspapers, and after the Second World War studied psychology, art and creative writing at college. He was spurred to publish his own magazine when refused a pay rise as a copywriter at Esquire.

Following the launch of Playboy magazine in 1953, Hefner became the epitome of the self- made man so admired in US society. His vision echoed the changing cultural landscape as post-war America boomed and mass consumerism became emblematic of the dominant world power.

An intellectual Playboy

In the early 1950s, most men’s magazines were outdoor-themed and championed the male bonding that emerged in the post-Second World War era over the likes of poker, bowling, hunting and fishing. “This had no real interest for Hef,” says David Goodman, CEO of Julien’s Auctions, who oversaw the March sale of Playboy memorabilia. “He wanted to distinguish his magazine from all the others and cater to the indoor guy instead – the intellectual, cosmopolitan male – focusing on the single life, the period of bachelorhood before you settle down.”

Ultimately, Goodman believes Hefner created Playboy because it was a magazine that he personally would enjoy, and because he saw no others in the marketplace aimed specifically at the stylish male singleton. Certainly, through Playboy’s pages and throughout his personal life, the entertainment mogul railed against the perception that men, married or otherwise, should be encumbered by convention. ‘The Playboy Philosophy’ advocated was, in his own words, “a moral maturity and honesty’’ in line with “adult tastes, interests and opinions”.

Mother knows best

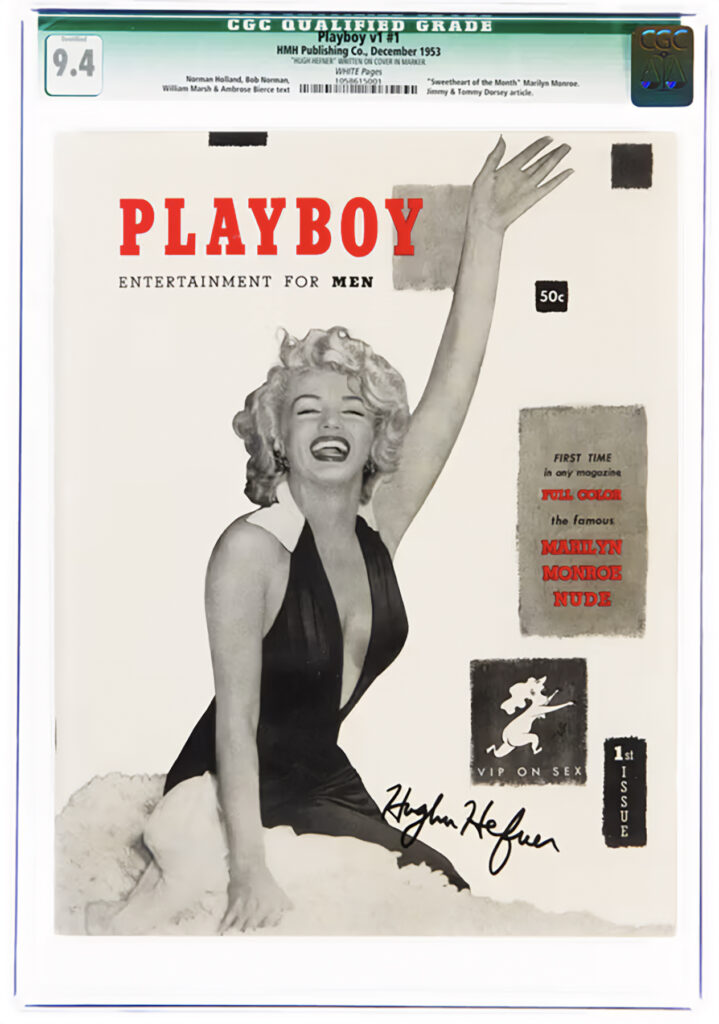

Raising the US$8,000 necessary to publish the magazine’s inaugural issue required some maternal support; his mother contributed a cheque for US$1,000. “His father said no, but his mother believed not necessarily in his venture, but in him,” reveals Goodman.

Setting the tone for a bold new publication, the first issue featured intimate portraits of emerging film actress Marilyn Monroe. They had been shot by celebrity photographer Tom Kelley, who then sold them to the John Baumgarth calendar company on Chicago’s West Side, close to where Hefner grew up. Knowing he needed a hook to create a buzz and attract readers, the fledgling publisher “drove out there in his beat-up Chevy, met with Baumgarth, and purchased the photos”.

Pin-up party

“Marilyn’s appearance in that initial issue and her now-famous response to the [nude] photos [being published], ‘I had nothing on but the radio,’ made a huge impact on the magazine’s success. Marilyn drew them in and the rest of the content kept them coming back,” says Goodman.

Playboy became synonymous with nude ‘pin-up girls’, and by rallying against America’s prevailing puritan values, it brought sex into the public forum. “It was Hef who believed that the pin-up could – and should – be acceptable in everyday life, right alongside art, culture, literature, et cetera. He rightly believed that the sexual nature of the pin-up wasn’t shameful and that our sexuality should be celebrated.”

Pushing boundaries

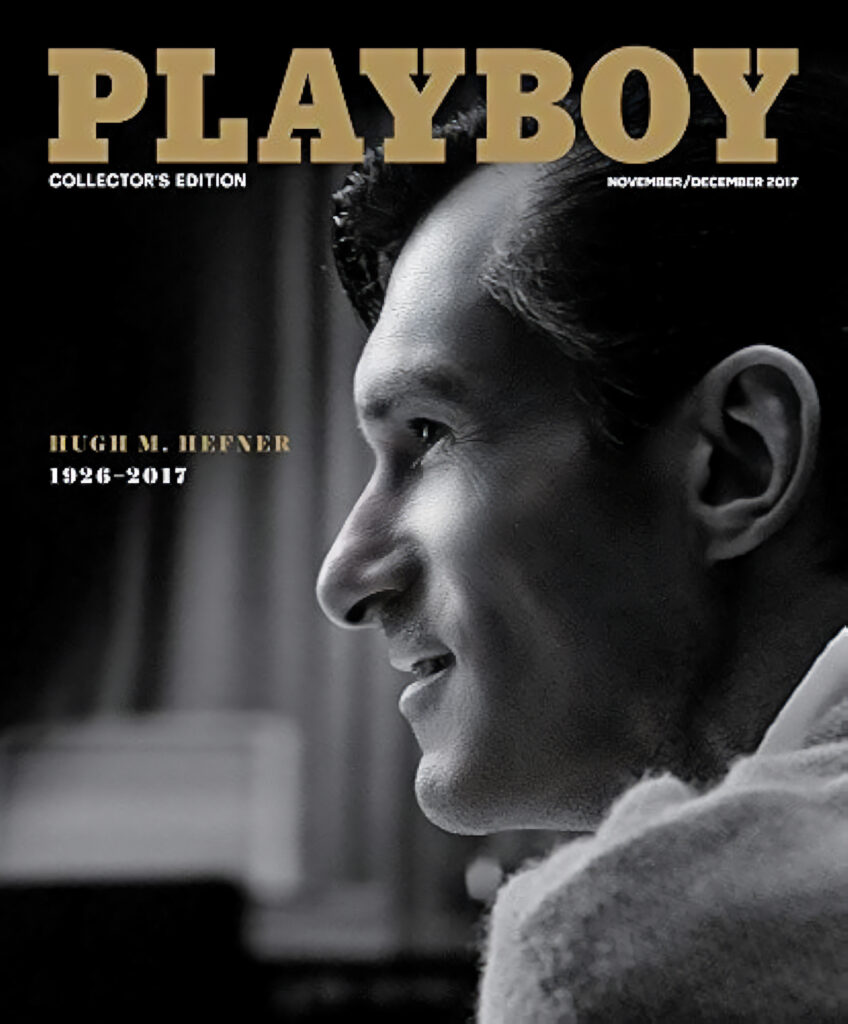

According to Goodman, Playboy had a profound influence on public opinion and the way we think as individuals. Upon Hefner’s death in 2017 at the age of 91, The New York Times obituary said as much: values long espoused in the magazine now reflected American society. However, it also noted that both the man and his brand were criticised over the decades as adolescent, exploitative and degrading to women.

Hefner’s track record on social issues of the day reads more positively. He was never afraid to embrace and defend unpopular opinions at the time, and his liberal ideals helped to advance progressive values and civil rights within society. Playboy interviewed Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Fidel Castro and Jimmy Hoffa, among many other momentous figures, and regularly covered topics that were considered taboo.

Leading the debate

From 1965, the issue of abortion was discussed in nearly every issue until the landmark Roe v. Wade ruling in 1973, and the Playboy Foundation began funding the abortion rights movement in 1966. “Letters from women were published, describing the emotional and physical pain they experienced from botched illegal abortions and, while Playboy’s stance was very clear, Hef let readers debate the issue publicly by printing responses monthly – both pro-life and pro-choice,” notes Goodman.

The magazine was ahead of public discourse on the issue of homosexuality, too: “Not only did people not discuss homosexuality [then], but the idea of a publication accepting it as an alternate lifestyle was revolutionary,” opines Goodman. It began editorialising about Aids before any other national magazine, educating its readers and bringing rational thought to the subject. Goodman says: “While the media was causing panic and prejudice by reporting on Aids as a ‘gay disease’, Playboy delved into the science, explaining that that’s not how viruses work – they don’t discriminate.”

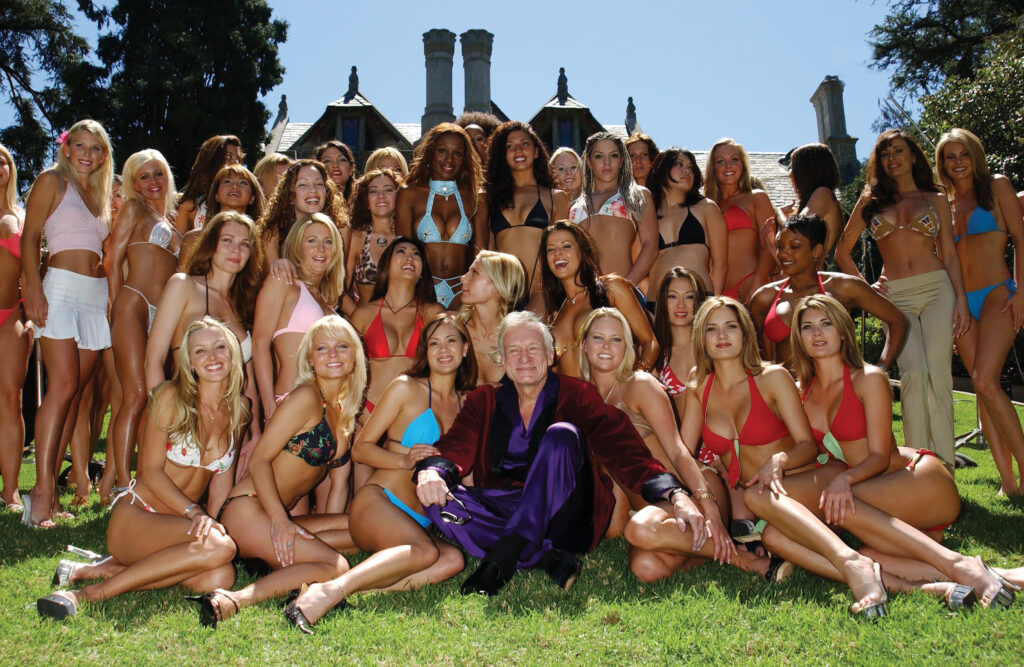

Club rules

On the back of the magazine’s early success, Hefner opened the inaugural Playboy Club in his home city in 1960. Scores followed in the US and even overseas, and they were notorious for their parade of scantily clad Bunny girls. Criticism grew that the concept objectified women and the clubs were closed by the late 1980s, but Goodman argues they performed a useful social purpose. “The Playboy Clubs were groundbreaking not only for the stylish and sophisticated atmosphere they provided their patrons but more importantly for the advancement of the civil rights movement,” he states.

“Members of all races were welcomed, as were performers, and Bunnies of all races were employed. Black musicians performed regularly, right alongside white performers. Aretha Franklin, then 18, got her start professionally at the Chicago Playboy Club. It was her first performance in front of a white audience, at the height of the civil rights movement.”

Hefner even bought back the franchises of clubs in New Orleans and Miami that refused to allow Black members. “This anti-segregation policy was at the heart of Hef’s ethos, and he would not stand for any deviation from it,” says Goodman. Black entertainer and activist Dick Gregory commented that “white folks weren’t exposed to [black comedians] until this fragile guy who smoked a pipe put us on stage”.

It was fitting that Julien’s auction united Hefner and his Playboy memorabilia with that of Marilyn Monroe. Both were symbolic of the sexual revolution in the 1950s and 1960s. Although the publishing magnate never met the actress during her short lifetime, they are close in death – he purchased the crypt next to hers in 1992 and is interred there. Whether he is resting easily is a matter of debate. As Goodman said of the recent sale, it was “about a time and a place that does not exist anymore”.