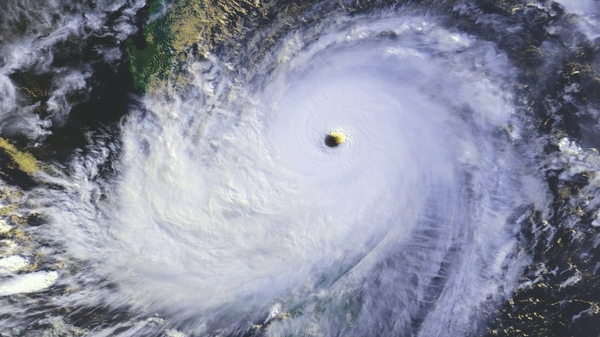

Global Warning: In the wake of Hato and Harvey, weather is a hot-button issue

With the world in turmoil, is the planet telling humanity, ‘Enough is enough’?

For many, the signs are clear. Hurricanes have battered the US as never before, while unprecedented floods have wreaked havoc in India, Bangladesh and Nepal, killing more than 1,000 and leaving millions homeless and hungry.

Meanwhile, wildfires of unprecedented intensity have scorched their way across huge swathes of the US, Canada, Greece, Portugal, Croatia, Greenland, Russia, Algeria and Tunisia. All the while, a dozen European countries baked and burnt as Lucifer, a suitably diabolically-named heatwave, sent temperatures soaring well beyond annual norms.

The weathermageddon was so severe that the massive floods and mudslides that devastated Sierra Leone and Niger went largely unreported, while the earthquakes that shook Japan and Mexico, as well as the severe drought that blighted the Ethiopian harvest, made few headlines beyond the local news.

Asia, too, was far from exempt. Flooding struck the south, and Hato proved to be one of the most destructive typhoons to make landfall on China for a generation or two.

The upshot of all of this? It’s no longer just the cranks and Gaia evangelists who are predicting a planetwide catastrophe. Indeed, an ominous silence emanates from the climate change deniers, with many of them now having firsthand experience of what happens when a global eco-system pushes back.

Speaking in the wake of recent events, Antonio Guterres, the United Nations General Secretary said, “Since 1970, the number of natural disasters has nearly quadrupled. This year, the United States, together with China and India, have experienced more disasters in any one year since 1995. On top of that, in the last year alone, 24.2 million people were displaced by sudden onset disasters – three times as many as by conflict or violence.”

It’s hard to dismiss the situation we find ourselves in. It was only on 23 August this year, after all, that Typhoon Hato churned its way through Hong Kong, Macau and Southern China, leaving 16 dead in its wake. When the signal 10 typhoon warning was hoisted – for only the 15th time since 1946 – it heralded not only incoming physical danger, but also a massive financial blow, with the city losing billions of dollars as the day’s trading was cancelled and workers were confined to their homes.

Despite another lesser storm – Pakhar – hitting the region just four days later, businesses and residents may take some comfort knowing that, according to the Hong Kong Observatory at least, the city may face fewer typhoons in the long-term. These adverse weather conditions, however, may strike with more intensity.

Outlining this change, Tong Hang-wai, one of the Observatory’s scientific officers, said, “It is highly likely that the global frequency of tropical cyclones will either decrease or remain essentially unchanged. Given that the overall climate is likely to be hotter, however, the warmer ocean will provide a higher level of moisture and energy, which will, in turn, fuel tropical cyclones. Overall, the mean sea level around Hong Kong will continue to rise, increasing the chance of extreme sea levels and heightening the threat of storm surge.”

While the term “storm surge” may sound innocuous when compared to “typhoon” or “hurricane”, such phenomena can actually do far more damage. Any combination of low atmospheric pressure and high winds can act to elevate the sea level and create monstrous tides, sometimes in excess of 8.5m in height.

This summer, another US weather record was broken, with two category four hurricanes making landfall across the country, the first recorded instance of two such occurrences in the same year. The first to arrive, on 25 August, was Hurricane Harvey, which saw Houston – the fourth most populous US city – flooded out, as a whole year’s worth of rain fell in a matter of days, leaving entire districts swamped and claiming the lives of 70 local residents.

With the post-Harvey disaster recovery process still underway, Hurricane Irma made landfall on 10 September. At one point swelling to the size of France, this second storm broke all records for strength and sustained wind speed, with its fury flattening villages in the Caribbean and leaving much of Florida submerged.

In perhaps the clearest sign yet of the global dysfunction of our weather patterns, while half the world dealt with an unprecedented deluge of rain, the other half baked in a prolonged drought, with water shortages and wildfires threatening crops and livestock. In parts of the US and Canada, a veritable inferno raged over the summer, destroying millions of acres of land and sometimes burning for months at a time.

In Portugal it was a similar story, with more than 60 people dying in the blazes that swept across the country in June. In Chile, meanwhile, its president called for calm as “the greatest forest disaster in our history” seared its way across the country.

While some countries burnt, others shrivelled in the unrelenting, unseasonal heat. In Ethiopia, 2 million animals died in the country’s long drought, while 8 million of its citizens faced an uncertain fate.

For many, it is a mystery just how these conflicting weather patterns can occur simultaneously. Two researchers – Friederike Otto, deputy director of Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute, and Maarten van Aalst, a director of Columbia University’s Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre – believe they may have the answer.

In an article jointly published earlier this year, the two concluded, “The warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapour, leading to extreme rainfall. At the same time, the higher concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere can also affect weather systems, with a lot of low pressure bringing rain. This could mean it does rain more, but in [unexpected] places.”

The science behind earthquakes is equally complex, with some researchers believing them to be triggered by the increased incidence of cyclones and unprecedented levels of rainfall. Regardless of whether it’s an earthquake, a wildfire or a hurricane, though, it’s impossible to prove a direct causal link between any individual natural disaster and man-made climate change. For many, though, the increased prevalence of freak weather and the unleashing of huge natural forces is proof enough.

Text: Emily Petsko

Photos: AFP