The Born Intensity: Baby boom turns to gloom, as nations face prosperity dips from declining populations

It was not so many decades ago that alarming stories of a global population explosion were commonplace and books such as Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb prophesised doom. The latest insights based on annual figures published by the United Nations paint a different story, however. Population implosion is now front and centre of many countries’ concerns.

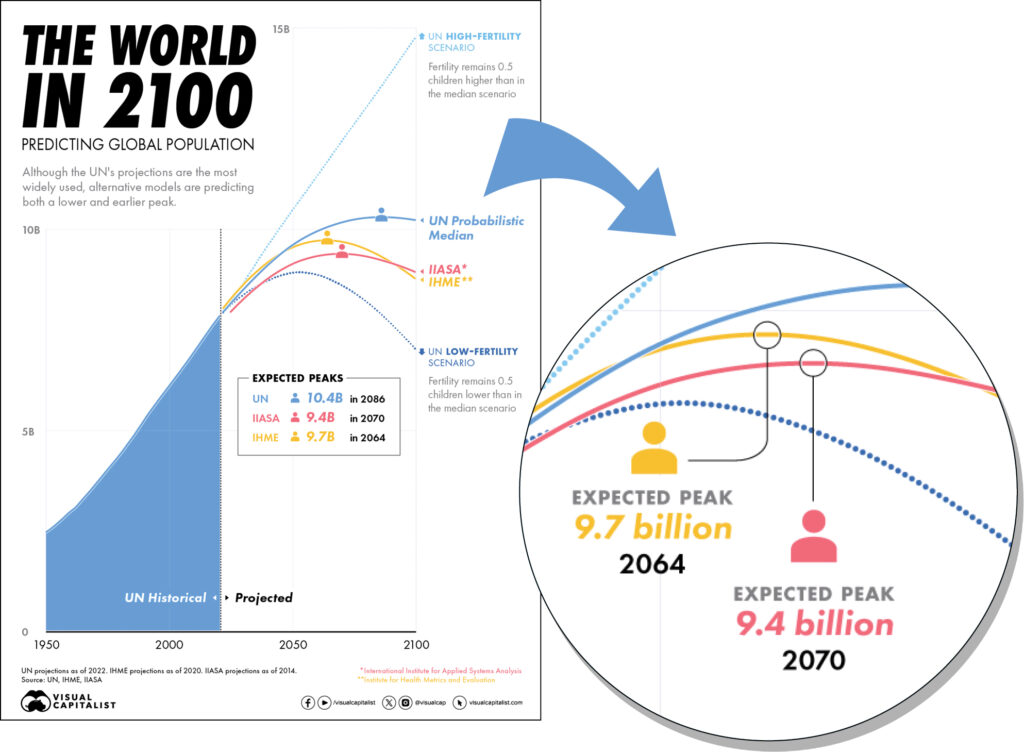

World Population Prospects 2024 outlines a predicted peak in the population on Earth within the current century at about 10.3 billion people in the mid-2080s, up from 8.2 billion last year. Indeed, one in four people globally now lives in a country where numbers have already reached their highest point – a statistic embracing 63 countries and areas containing 28 per cent of the world’s population. Some analysts believe this could have damaging consequences for social and economic progress in the likes of China, Japan, South Korea and many European nations that are already experiencing severe demographic challenges.

Fertility fall

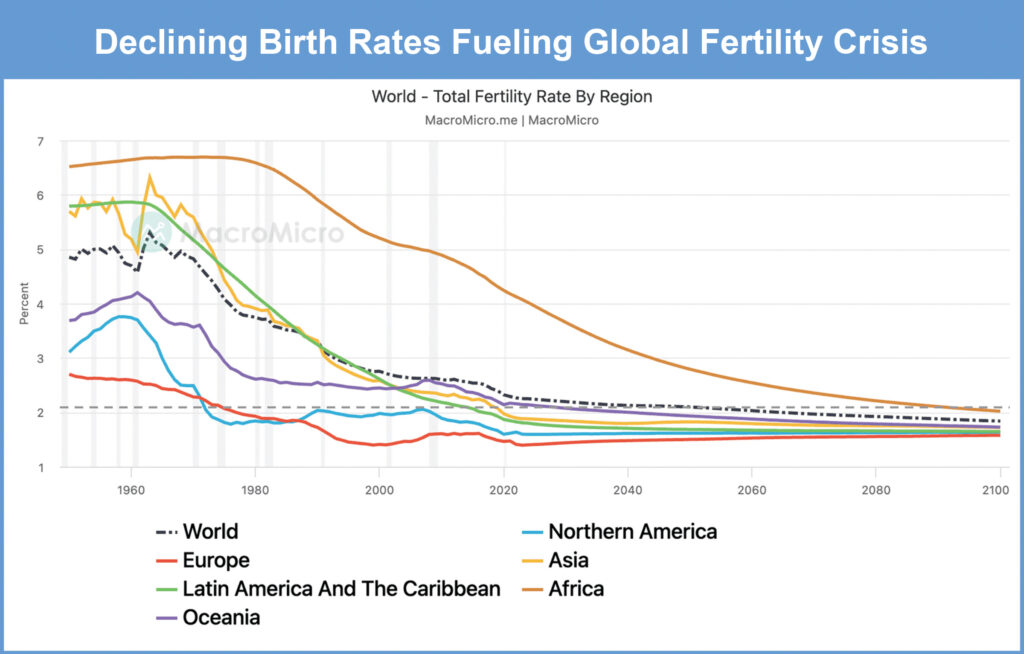

A major cause of population decline is the low birth rate across many countries, a trend that has existed for decades in some cases, especially in Europe. As early as 1970, demographers had noted total fertility rates in 19 countries had fallen below the replacement level of 2.1 births per women – the number required for a population to maintain a constant size without migration.

According to the latest UN estimates, women today bear one child fewer, on average, than they did three decades ago, and more than half of all countries and areas globally have fertility below the replacement level. Currently, the global fertility rate stands at 2.3 live births per woman, down from 3.3 births in 1990.

Reduced fertility generally occurs as countries become industrialised and experience a fall in mortality and a consequent population growth, a cycle that ends when the population implements fertility control. Leading demographers such as Tim Dyson note that fertility decline has liberated women from the domestic domain. As such, their lives have become increasingly similar to those lived by men, and marriage in the sense of a life-long commitment to have and rear children is seen as increasingly unattractive. In summary, demographic history suggests that as societies become richer, people tend to have fewer children.

Ageing expensively

Highlighting the pressing nature of declining population, the number of babies born in the European Union hit a record low in 2023. The 5.5 per cent drop from the previous year was the sharpest ever – a scenario expected to heap pressure on state finances due to the shrinking size of the working population, coupled with the rising cost of healthcare and pensions in an ageing population. According to demographic experts, the trend of lower birth rates in Europe since the mid-’60s has been exacerbated by fears over climate change, inflationary pressures, and political and job uncertainty.

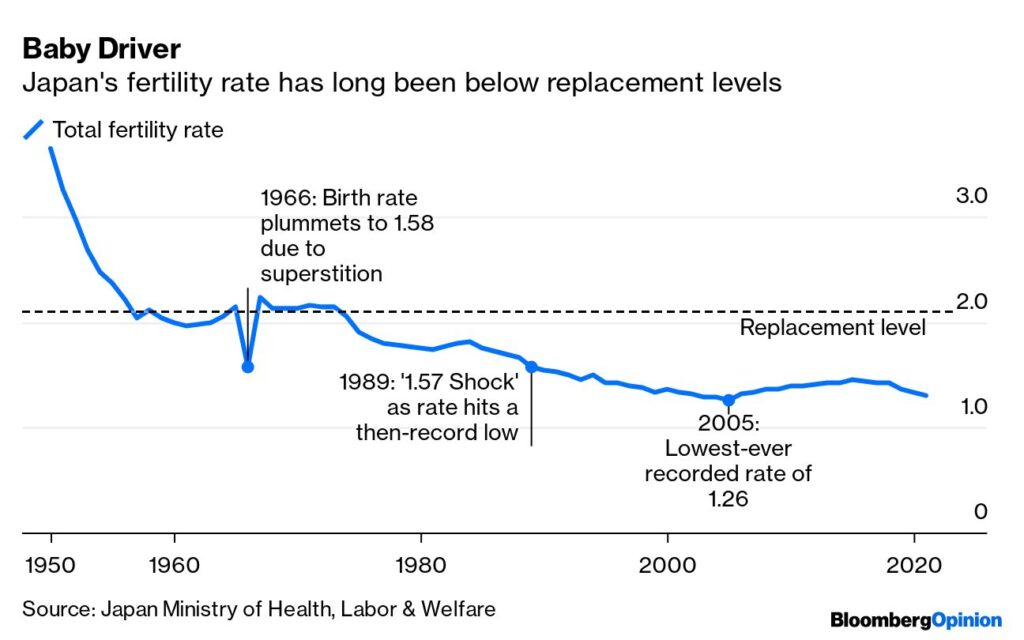

Willem Adema, a Senior Economist at the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), notes that some young people have difficulties establishing themselves in the labour market, the housing market and “perhaps also in the dating market”. This comment will have particular resonance in Japan, which is experiencing a similar, if not worse, demographic timebomb than Europe.

Dating decline

Despite increased numbers of foreign residents, Japan’s total population has declined for 15 years in a row. In 2022, when the number of newborns fell below 800,000 for the first time since records began, the figure was 122.42 million and it is expected to drop further over the coming decades. The government has gone to the extraordinary lengths of consulting young people in a bid to understand their reasons for not marrying. It recently set up a Children and Families Agency to help young people find the love of their life through dating, matchmaking and other services.

According to a 2023 survey, more than 40 per cent of marriages in Japan were sexless, and fears are mounting that this apparent lack of sexual desire has percolated down to the younger population, further endangering the deteriorating birth rate. Izumi Tsuji, a Professor of the Sociology of Culture at Tokyo’s Chuo University, cited the many other distractions and hobbies of the younger generation as one reason for the decreasing value placed in dating. This latest revelation could compound concerns about a seeming unwillingness by Japanese people to marry, despite a government raft of child support packages.

Baby boost

A reluctance to get married and falling birth rates in Hong Kong have also prompted much debate. Just 32,500 births were registered in 2022, the lowest number since records began more than 60 years ago; in 2019 that figure totalled 52,900. In one particularly inventive plan to address the problem, lawmaker Bill Tang Ka-piu suggested that the prominent display of baby pictures in government offices would spark procreation among the city’s civil servants.

Hong Kong’s declining birth rate has been attributed to factors including current restrictions on in vitro fertilisation (IVF), the prevalence of divorce and a lack of supportive measures for single parents. A HK$20,000 cash bonus introduced by Chief Executive John Lee Ka-chiu for parents of new-born children appears to be helping reverse the trend: the number of births increased by 9.8 per cent year on year following the October 2023 launch of the handout.

Such concerns are being played out across much of the developed world. In the United States, the fertility rate is 2.08 children per woman, which is creating issues in this vast country. As people internally migrate to more prosperous areas, some places are being catapulted into ghost towns. Caught in a so-called death spiral, fewer locals then remain to pay local taxes, which exacerbates a worsening situation for those left behind.

One no longer enough

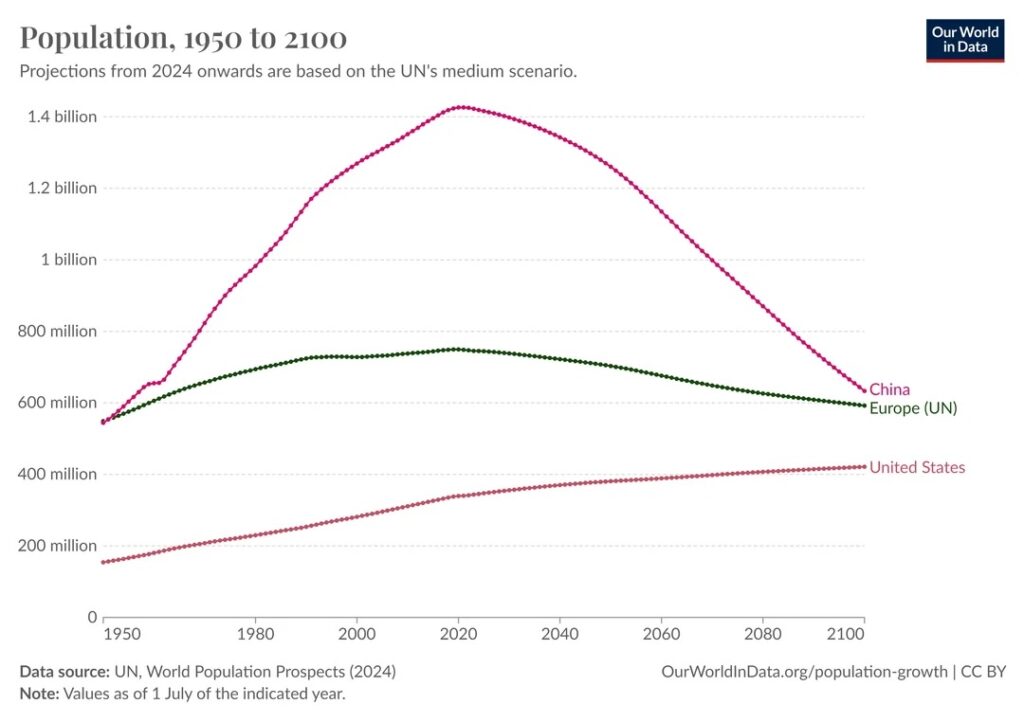

China famously introduced a one-child policy in 1979 in a bid to control a burgeoning population. Overpopulation was then viewed as a threat to economic growth and a harbinger of social and environmental problems. Beijing’s population control measures were successful in the sense that demographers suggest that by the year 2000 there were 300 million fewer people in the country than otherwise would have been the case.

The one-child policy was abandoned in 2016, and like many parts of the West, China is faced by major demographic challenges as its population ages and shrinks. In 2023, only about nine million births were recorded, the lowest since 1949, and the total number of inhabitants fell for the second consecutive year. With a fertility rate of about 1.0, far short of the 2.1 replacement level, the national government has rolled out numerous incentives for families with multiple children.

Benefits of youth

According to Jeffrey Wu, Director of Hong Kong-based firm Mindworks Capital, how China navigates its demographic shift will define its economic future – it is that fundamental. To cope with the challenge, a huge boost in productivity will be needed, aided by technological innovation and capital and human capital investment. Automation and artificial intelligence, it is hoped, could potentially be a boon to productivity.

This is a noble aspiration because one potential effect of a nation having fewer young people is weaker innovation and growth. A 2021 study into patents by US research organisation NBER (National Bureau of Economic Research) highlighted that the youngest inventors were those most likely to produce novel, groundbreaking work that could raise productivity substantially.

Ultimately, many countries will use immigration to mitigate the demographic shortfall. As the UN suggests, those still with youthful populations but declining fertility have limited time to benefit economically from an increasing concentration of working-age citizens. In order to capitalise on this opportunity, investing in education, health and infrastructure, and implementing reforms to create jobs and improve government efficiency are essential.

Of course, population decline also has its benefits, particularly in reducing the pressure on global resources and the environment – something China’s President Xi Jinping, among others, has alluded to. This is a theme that will undoubtedly be taken up in the years to follow.