Lost Property: Disputed colonial-era treasures long held by museums in the West begin the journey home

From the late 15th century when the Western colonial powers held sway over vast swathes of the world, hordes of precious artefacts were seized as spoils of war or amassed in other ways. Many were sold privately and larger numbers still ended up in the great encyclopaedic museums of Europe.

As territories gained their independence following the Second World, they began to voice a desire for the return of cultural treasures that had been looted, purchased or gifted. Arguments about the legitimate ownership of such heritage pieces are long and complex, but in recent years Western governments and institutions have begun to heed a groundswell of public opinion and make accommodations for some to head back to their original home.

In the UK, the issue is complicated by a law that prohibits national museums from permanently handing over items in their collections. To circumvent this legal hurdle and find common ground, a collaborative approach is required.

Contested marbles

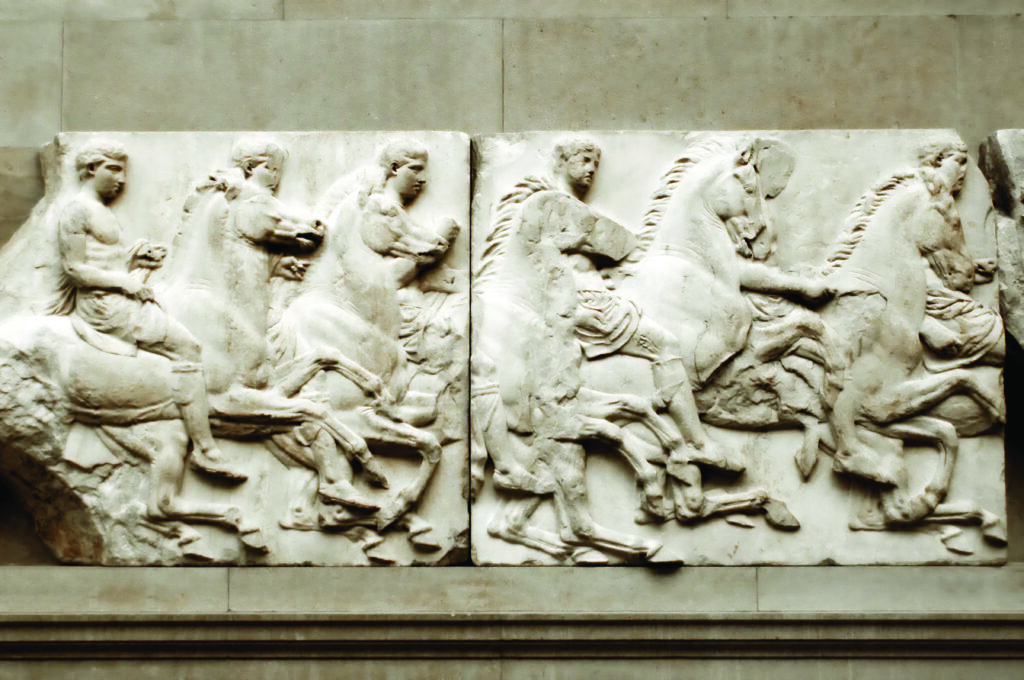

It was reported last year that the British Museum had engaged in talks with Greece over the fate of the Parthenon sculptures. The Elgin Marbles, as they are known in the UK, are perhaps the most famous of the contested colonial artefacts in the museum’s collection. The Parthenon, ancient Athens’ most important temple, sat atop the Acropolis and was decorated with marble statues and a sculpted frieze depicting heroes and gods at a festival in honour of the goddess Athena.

The exact circumstances surrounding permission in 1801 for British ambassador Thomas Bruce, the Earl of Elgin, to remove “some pieces of stone with old inscriptions and figures”, as he put it, have been debated ever since. At a UK parliamentary committee convened in 1816 to investigate the possible purchase of the marbles from Lord Elgin and assess their worth, British sculptor John Flaxman called them “the finest works of art … [and] the most excellent of their kind that I have ever seen”.

Cultural commentators are divided on the issue of important national symbols – as the Parthenon Marbles are to the Greeks – residing in institutions that belong to another country. Many believe there is a strong moral argument for the repatriation of cultural treasures acquired during colonial times. Indeed, in a poll last year, the majority of the British public supported the marbles’ return to Greece in a cultural partnership.

British sociologist Tiffany Jenkins, author of the book Keeping their Marbles, believes the Elgin Marbles perform a valuable service by sitting in the British Museum, where a reported 75% of visitors are from overseas. When viewed there, in context with galleries showing artefacts from the Roman Empire, for instance, it is possible to see the influence the Parthenon had on other cultures.

The Greek government has sought the return of the marbles from Britain for more than 40 years. The remaining Parthenon sculptures reside in a state-of-the-art museum next to the Acropolis, where a place has been reserved for those removed by Elgin. It is thought the Greeks wanted to strike an agreement that would mean masterpieces like the mask of Agamemnon could be shown in the UK for the first time.

Regalia return

The British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) announced details in January of a long-term loan agreement whereby gold and silver regalia from the ancient Asante royal court will be displayed at the Manhyia Palace Museum in Kumasi, Ghana. These artefacts are of cultural, historical and spiritual significance to the Asante people and the announcement was greeted with joy by Ghanaians; many of the objects will be seen in the country for the first time in 150 years. The collaboration follows an official visit to London by the Asantehene (King of Asante) Otumfuo Osei Tutu II in May last year.

“We are delighted to be lending these beautiful and significant cultural objects for display in Kumasi in this the Asantehene’s Silver Jubilee year and the 150th anniversary of the Anglo-Ashanti war, and to be doing so through a collaboration with Manhyia Palace Museum and the V&A,” said Lissant Bolton, Keeper of Africa, Oceania and the Americas at the British Museum.

Items from the British Museum collection include those looted during a later conflict, in 1895-1896, as well as gifts to the museum presented during trade negotiations in the early 19th century. Among them are the Mpomponsuo sword of state and a small gold ornament in the form of a lute-harp (sankuo).

For its part, the V&A is lending 17 objects, including all 13 pieces of Asante royal regalia it acquired at a Garrard auction in 1874. Standouts are a gold peace pipe and three gold soul-washers’ badges (akrafokonmu) that were worn around the necks of court officials responsible for cleansing the king’s soul.

Moot loot

A report commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron in 2018 called for thousands of African artworks in French museums taken without consent during the colonial period to be returned to the continent. France duly gave back 26 objects to Benin from a collection known as the Abomey Treasures that were looted by French forces in 1892 – including statues, portable altars, palace doors and a throne. The gesture was part of French moves to improve its image in Africa and allow Africans access to their heritage.

Belgium is also making strides to repatriate many items taken during its colonial occupation of the Congo. King Philippe recently handed over a magnificent large wooden mask to Félix Tshisekedi, President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Other items are set to follow.

Now scattered in museums in the UK, the US, Germany and elsewhere, the Benin Bronzes are another collection of artefacts whose repatriation in some form have been urged. These superb royal and personal objects crafted from the 16th century onwards at the behest of the court of the Oba (king) in Benin City (in modern-day Nigeria) include elaborately decorated cast plaques, commemorative heads, and animal and human figures.

The 1860 plunder of Yuanmingyuan (the Old Summer Palace) in Beijing left a treasure trove of Chinese art and artefacts in British hands. Years later many were sold at auction houses and found their way into museums. Unesco has estimated that about 1.6 million Chinese relics are in the possession of 47 museums worldwide, including about 1 million looted from Yuanmingyuan. Chinese antiquarians believe more than 10 times that number are in the hands of private collectors. Some of these precious heritage objects are now being bought by wealthy Chinese and returning to China. The fate of the remainder is open to speculation.

India pride

India has been hankering since independence in 1947 for the return of the Koh-i-Noor diamond acquired by Britain during colonial times from the 10-year-old Maharajah of Punjab. Following its arrival in Britain, the Koh-i-Noor was eventually cut by Dutch master craftsmen in perfect symmetry with 33 facets on top and the same number underneath. Widely lauded for its dazzling beauty, the diamond was set in successive royal crowns, most lately that of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother. Pakistan has also laid claim to the jewel.

One interesting development, which organisers are hoping will provide a new model for sharing art across borders, is an exhibition at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya in Mumbai, India of items on long-term loan from the British Museum, the Berlin State Museums and J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. On display until 1 October 2024, Ancient Sculptures: India, Egypt, Assyria, Greece, Rome brings great works of antiquity from Western museums to an Indian audience and helps shed light on the interconnectivity between religions and cultures since ancient times.

“We see the exhibition as a unique and important educational endeavour that provides our Indian audiences and children with new ways of viewing their own culture as a result of seeing it in relation to other societies and geographies,” said Sabyasachi Mukherjee, director general of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, Mumbai, also noting that a high percentage of India’s young people might never have the opportunity to travel and experience the art and culture of other parts of the world.